War Stories | by Jay

Veteran's Day is today, and with the added bonus of us playing Navy tomorrow, we thought this would be a nice opportunity to highlight a couple of stories from the rich history between Notre Dame sports and the U.S. armed forces. (Thanks to BGS contributor Will for putting this article together.)

ND's association with the armed forces goes all the way back to 1858, when the student-organized Continental Cadets began marching across campus. Since then, thousands of domers have served in the US military.

World War I. From a ND Magazine article by John Monczunski:

The initial campus enthusiasm for military training abated following the Civil War, but in 1880 University President William Corby, CSC, the famous chaplain who gave absolution at the Battle of Gettysburg, revived the program. Father Corby believed a military regimen would offer Notre Dame students an excellent source of recreation, exercise and discipline. The new Notre Dame cadets, sporting gray uniforms, came to be known as Hoynes Light Guards, after the professor charged with overseeing the unit, "Colonel" William J. Hoynes. Two years later, academic credit was offered for the training. By 1917 it had become a required course for most Notre Dame students.

That same year, the University administration applied to the War Department to participate in the government's Student Army Training Corps (SATC), the forerunner of today's Reserve Officers' Training Corps (ROTC). With the World War I draft draining away students, administrators saw participation in SATC as essential to the economic viability of the school.

Notre Dame cadets practiced marksmanship at a firing range between Corby Hall and Old College and marched and drilled, but the training was judged inferior by the government and the bid rejected. Notre Dame President Rev. John W. Cavanaugh, CSC, was furious with the verdict. The University continued to lobby, and in autumn 1918 some 700 students were sworn into the SATC, only to be demobilized in December with the war's end. More than 2,200 Notre Dame students and alumni served in the armed forces during World War I.

Naval Reserves Come to ND. World War II: Most American companies and institutions were devoting all possible resources to the war effort, and Notre Dame was no different. Prior to the Pearl Harbor attack, the Naval Reserve Officers Training Corps became the University's first ROTC detachment. (Father Hugh O’Donnell initially offered the Army the use of University facilities, but they declined.) The Navy gradually began expanding their presence on campus, adding a Midshipmen's School and the V-12 Program, which began in 1943 and introduced the Marine Corps to campus.

Naval Reserves Come to ND. World War II: Most American companies and institutions were devoting all possible resources to the war effort, and Notre Dame was no different. Prior to the Pearl Harbor attack, the Naval Reserve Officers Training Corps became the University's first ROTC detachment. (Father Hugh O’Donnell initially offered the Army the use of University facilities, but they declined.) The Navy gradually began expanding their presence on campus, adding a Midshipmen's School and the V-12 Program, which began in 1943 and introduced the Marine Corps to campus.By the middle of the war virtually the entire campus was military, and for all practical purposes, Notre Dame was now a naval base. The only exceptions were 250 17-year-olds who were too young for the draft, and a handful of civilians classified as 4F. Over 12,000 naval officers would end up departing the peaceful shadow of the Golden Dome for the battlefields of World War II.

Thomas J. Schlereth, historian and professor of American Studies at Notre Dame:

"The war years inextricably changed Notre Dame. Contracts came from government research. A speedup cafeteria system in the South Dining Hall replaced the form of family-style dining, feeding twice as many men in half the time, with much less than half the former intimacy and civility. The public 'caf' overflowed with military brass, WAVES, and recruits whose campus stay often extended only months rather than the usual four years. Vacation periods were abbreviated, classes accelerated, semesters shortened, and one year there was no Christmas holiday. Women appeared all over the previously all-male, semi-cloistered campus, replacing undergraduates who formerly had done part-time jobs in offices, dining halls, laboratories, and the library. Sentries patrolled the campus perimeters at night; long blue, white and khaki lines tramped the quadrangles by day."The ’43 football team reflected the military make-up of the campus, with the roster now listing the military status of each player: Marine Reserve (14), Naval Reserve (12), Civilian (4), 17-years-old (9).

To this day, a large part of why we continue to play Navy every year in football is because during World War II, if not for the Navy, ND would have probably had to shut down.

Angelo Bertelli

Angelo BertelliThe quarterback of the ’43 team, Angelo Bertelli, left the team 6 games into the season after being activated by the Marine Corps. Bertelli learned that he had won the 1943 Heisman Trophy when he was given a telegram in a boot camp in Paris Island, S.C. After boot camp, Bertelli was made a captain and saw combat on Guam and Iwo Jima.

During a battle on Iwo Jima a fellow corpsman was wounded by a mortar blast that had also landed near Bertelli. Bertelli recalled sadly that a newswire service reported the All-American’s health status without ever mentioning that a fellow corpsman was almost killed in the same combat incident. Bertelli was awarded the Bronze Star and the Purple Heart for his heroics in the war.

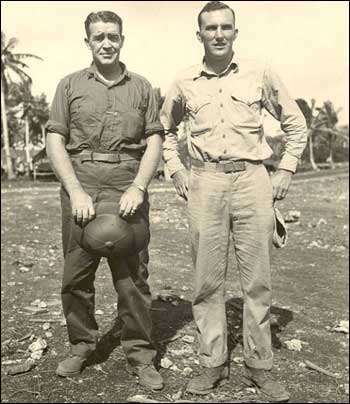

|

| Leahy & Bertelli in the South Pacific |

Early in 1944, George's V-12 unit was called to active duty. He was commissioned an ensign and assigned to a subchaser in the Pacific, which eventually docked at Pearl Harbor. A command car pulled up to the dock and a Navy sailor approached the ship and asked where he could find Ensign Connor. Connor, who was the one he asked, said, "I am Ensign Connor." The sailor said, "Sir, I have been sent here by Commander Leahy, who requests that you meet him at Navy headquarters right away ."Leahy wasn’t the only Notre Dame coach to join the war effort. In fact it was basketball coach Moose Krause that convinced Leahy to sign up along with him. The following is compiled from stories contained in Jason Kelly's Mr. Notre Dame, the story of the life of Notre Dame's Moose Krause.

Connor went below, changed uniforms, and was driven to headquarters. He explains what happened. "I met with Coach Leahy, who was very cordial and inquired as to my well-being as well as my family. Then he said, 'George, I wanted you to come to Notre Dame when you graduated from high school and I want you to come to Notre Dame after the war. If you come there, I can promise you two things: we will win the National Championship and you will be an All-American.

In 1943, Moose Krause was named the head coach of the men's basketball team, officially replacing the recently deceased George Keogan. In addition to his hoops duties, he was also an assistant coach on Frank Leahy's football team. However, as more and more players were being called into active service, Krause knew that enlisting in the military was the right thing to do. He also convinced Leahy to join him, reminding him that in addition to patriotic reasons, it would be hard to earn the respect of the returning veterans sure to fill the Irish rosters after the war if they did not contribute as well.

Krause joined the Marines and was sent to the island of Emirau in the South Pacific as part of the Marine Bomber Squadron 413. His official assignment was a combat intelligence officer charged with planning safe and effective air raids. He also took on the unoffical task of base morale officer. He constructed an officer's club and basketball courts on the island to keep the soldiers upbeat and fit. He also assisted as much as he could with the base chaplain, Rev. James Gannon.

Krause also befriened the native Moro who lived on the island. In return for his friendship, the Moro volunteered to spy on the nearby Japanese. Moose would regularly take a group out on a boat at night to the Japanese held island of Rabaul and retrieve them a day or two later. One night, Krause and Gannon were informed by the Moro that the unburied remains of six Marines were found on the island. Krause and Gannon then set out on a mission to provide a proper burial for their fellow soldiers. They snuck onto the island and retrieved the bodies but could not return to their boat before nightfall. The Moro people led them to a remote village with the promise the Japanese would not discover them while they slept. In the morning, Krause and Gannon found out the reason; they were staying in a leper colony the Japanese avoided. After leaving the island with the bodies and burying them in Emirau's cemetary, Krause and Gannon then sent supplies of clothing, medicine, and food to the leper colony that hosted them for the night.

The war ended shortly thereafter and Moose returned to the States and resumed his coaching jobs back at Notre Dame.

Motts Tonelli. By far the most amazing story involving a former Irish football player in WWII is that of Mario ‘Motts’ Tonelli. (You can read the entire account here.) Tonelli played on the Irish teams of the late 30’s, scoring the game winning touchdown against Southern Cal in 1937. He graduated from the University in 1939 then went on to join the Army in ’41. He was assigned to a regiment in Manilla. After the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, Tonelli was ordered to retreat to Bataan along with 15,000 other American military personal. Tonelli was then captured by the Japanese and forced to set off on the now infamous Bataan Death March.

On the first day of the seven-day 70-mile death march in April 1942, Japanese soldiers swept up and down the ranks, confiscating pens, jewelry or other personal possessions from the lines of struggling U.S. prisoners. One captor pointed with his bayonet at the ring on Tonelli's finger. "Give it to him, Motts. Or he'll kill you," whispered one of Tonelli's friends. Tonelli handed over the ring.Jack Chevigny. Perhaps the strangest story of a former Fighting Irish gridiron star and WWII is that of Jack Chevigny. Chevigny was from Chicago and starred on Knute Rockne’s great teams of the late 20’s. He scored a touchdown against Army in 1928, the game in which Rockne gave his now-famous “Win one for the Gipper” speech. As Chevigny crossed the goal line he shouted “That’s one for the Gipper!”.

Tonelli as a fullback Tonelli in a Japanese prison camp

Moments later, a Japanese officer confronted Tonelli. In perfect English, he asked, "Did one of my soldiers take this from you?" The officer pulled the ring from his pocket. "I went to the University of Southern California," the officer said. "I graduated the same year you did. In fact, I saw the game when you made that long run that beat us. You were a hell of a player." "He gave me my ring back and wished me good luck," Tonelli recalled many years later.

In 1934 he was hired to become the head football coach at Texas. During his first year he beat Notre Dame which inspired a gift from the Longhorn fans, a fountain pen with the inscription “to an old Notre Damer who beat Notre Dame.”

When WWII started, Chevigny signed up for the Marines and became an officer. Chevigny died at Iwo Jima but his fountain pen would go on to play an important role in history. When the officers of Japan and the U.S. met aboard the U.S.S. Missouri to sign the truce signifying the end of World War II, a naval officer noticed a Japanese officer signing the documents with a shiny gold fountain pen with an inscription on it.

The officer asked to see the pen, and read the words, "to an old Notre Damer who beat Notre Dame." Aware of the legacy of Chevigny, the officer put the pen in his pocket and took it back to Chicago, and found Chevigny's sister and gave her the pen, which must have been taken from Chevigny's body during the battle where so many died.

Rocky Bleier. Rocky Bleier was a 5-9, 210 lb running back on the 1966 National Championship team, and a captain during his senior year in ’67.

After leaving Notre Dame he was a 16th round draft pick of the Pittsburgh Steelers. Following his rookie season with the Steelers, Bleier was drafted and shipped off to Vietnam.

Bleier explained, “What were my options? Go to Canada? Get into the reserves? Injure myself? Ask for status as a conscientious objector? I couldn’t get into the reserves. I got drafted. I go.”

On August 20, 1969, his platoon was ambushed in a rice paddy near Chu Lai, and Bleier was wounded in his left thigh. While he was down, a grenade exploded nearby, sending pieces of shrapnel into his right leg and foot. After recovering from the injuries, Bleier showed up at the Steeler’s 1970 training camp 30 pounds under his previous playing weight and unable to walk without pain and a noticeable limp.

Even after being cut twice by Pittsburgh, Bleier never gave up. After struggling for several seasons to find a spot on the Steelers’ roster, he rushed for more than 1,000 yards in 1976 and caught the decisive touchdown pass in Super Bowl XIII. Rocky Belier would go on to play twelve seasons in the NFL, winning four Super Bowls and retiring as the fourth leading rusher in franchise history.

Again, thanks to Will for compiling these stories.