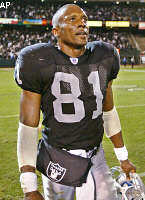

81 | by Jay

It’s those kick returns. The football equivalent of a one-punch knockout, except that it is more deliciously anticipated, or at least awaited, yet always a surprise when it happens.

It’s those kick returns. The football equivalent of a one-punch knockout, except that it is more deliciously anticipated, or at least awaited, yet always a surprise when it happens.

The ball floats skyward while down below nearly two dozen bodies perform a confused choreography. Sometimes the bodies fan out – either to pursue No. 81 or, depending on their alliances, to throw a miserable two-second block – two seconds? – on his behalf. Sometimes they converge at midfield, a dangerous clot of tacklers zeroing in on this poor man with the ball. Once in a while it’s an awful collision, the kick catcher looking up from the ball just in time to collect 230 hurtling pounds in his face mask. Usually in this game, the play ends with a whimper, the victim slowed by the gauntlet and eventually buried harmlessly in a pile.

But sometimes, more often with Tim Brown than anybody in the country, this muddle down below becomes suddenly transformed. This particle emerges from the mid-field jumble with an astonishing suddenness. The acceleration is breathtaking. “Like a draft when he goes by you,”

No two of these are ever alike. Last week, against Air Force, Brown simply smashed up the middle to open field, or mostly open field. The punter remained lamely holding the fort. Punters are the worst.

“It can be kind of pitiful,” Brown agrees. “But I don’t think they open their eyes anyway.”

Or perhaps, as against

“Sometimes I break tackles, sometimes I run by people,” he says, trying to be helpful. Explanations, though, are exasperating. “I find it hard to explain. I really don’t know what’s going on, except I’m trying not to get hit.”

It is one of football’s greatest sights, Tim Brown not getting hit. Picture it.

--

What picture sticks in your mind when you think of Tim Brown, Irish football hero, Heisman Trophy winner, and surefire lock for the NFL Hall of Fame?

He was of average build for a receiver, about six feet, one-ninety, and he wore oversized shoulder pads fit for a lineman. He caught passes, mostly over the middle, and somehow, with a juke and a cut he’d make you miss, and turn a ten-yard toss-and-catch into a seventy yard romp into the endzone. He got open – a lot. And he caught everything.

He was fast, but he wasn’t a sprinter. He had shifty moves; his hips seemed to go one way while his body went the other. His remarkable peripheral vision enabled him to see the entirety of the field, his eyes anticipating danger, and he’d adjust and change course in a split second.

He was a triple threat, taking handoffs, catching passes, and fielding kicks and punts. He pioneered the importance of “all-purpose yards”, and single-handedly made the stat famous.

And even when he didn’t touch the ball, he changed the dynamic of the game, drawing double (and triple) teams to open up other options, inducing short punts and squib kicks, throwing blocks downfield to help out his teammates.

Off the field, he was contemplative and analytical, with a strong faith and a real dedication to the guys in the locker room. Incredible work ethic. Great sense of humor.

The superlatives that resonate: hardworking, humble, smart, versatile. One of the all-time greats, and for many Irish fans, their absolute favorite player, ever. He had a combination of intense competitiveness and sincere modesty that’s so rare these days, and it’s no exagerration to say that Tim was good at everything he did, on and off the field. As Lou Holtz once said, “He’s special. He’s the type of guy, you’re around him just a few minutes and you can tell: he isn’t average. He’s isn’t an average athlete, and he isn’t an average person.”

And now, amazingly, it looks like we’re getting the legend back. The rumor’s been floating for about a week or so, but on Saturday Tim confirmed that he was in talks to return to Notre Dame in some capacity, probably as a co-recruiting coordinator or a player liaison. He may moonlight as a NFL receiver for another season or two, but come next year, he’ll be working for his alma mater once again.

And so, in light of this excellent news, we thought we’d take the opportunity to pay a little tribute to one of our favorites, No. 81.

--------

“You know how moms are.” -- Tim Brown.

When Tim was a kid growing up in

He grew up in a very religious family, and his mother, Josephine Brown, had a career path worked out for young Tim: go to college, become a Pentecostal minister.

(Even at the Heisman ceremony, right there in the Downtown Athletic Club, as the award was being presented, Mrs. Brown pushed the idea. “I love my son. I’m proud of him. But one day, he will give up football and become a minister. I really believe that,” she said to the reporters. For the record, Brown doesn’t reject the idea, but he seems to relegate it to later in life. “When the time comes, I will make that decision. But right now, I’ve got to do what’s in front of me.”)

Josephine objected to competitive sports, so she forbade her 5’4” son from playing freshman football in high school. Tim joined the band instead, but after a year he dropped the bass drum in favor of a helmet and shoulder pads, getting his father Eugene to sign the permission slip, unbeknownst to his mother.

“He kind of slipped football on me. Until the band leader called wanting to know why he was skipping practice, I was still thinking he was in the band,” Josephine said.

“The old band story,” said Tim. It worked.

Woodrow Wilson High had only 25 players on their varsity squad, and they were terrible, winning a grand total of four games in Tim’s career. Still, Brown was a standout. “I played wide receiver and running back, returned kickoffs and punts and also played quarterback and free safety. And I played them pretty well. I think that was a big eye-catcher for the recruiters.” He scored 25 touchdowns in his variety of roles, but the team never enjoyed success.

“Possibly it’s because when a bunch of guys think more about getting drunk than playing football, that’s what happens. They just had other aspirations, things they concentrated on, and football wasn’t one of them,” he remarked.

Funnily enough, Brown was also the sports editor of the school paper (and was elected VP of his senior class), and he often found he had to write feature stories about himself. Too modest to print a byline, he wrote them anonymously. “I always ended up writing about myself, but I tried to act like someone else wrote it when I wrote about games I played in. I wouldn’t put my byline on the story. But everyone knew who the sports editor was.”

“I really thought I was going to end up at SMU. I’m definitely glad I didn’t end up going there. In the end, I figured if football didn’t work out and I had to have something to fall back on, a Notre Dame education was best," Tim said.

ND was overjoyed. Assistant coach Jay Robertson, who had recruited him, was effusive in his praise: “He was phenomenal – like smoke through a keyhole. He had the sixth sense of anticipating where trouble was. And he had the quickness and athletic ability to get away from it."

(By the way, is "like smoke through a keyhole" one of the most evocative descriptions you'll ever hear about a football player? I'm still not sure what it means, but it seems so damn cool.)

“He’s a thrill to throw to. I can toss a five-yard pass and I never know what’s going to happen.” -- Terry Andrysiak

Brown arrived on Campus in the fall of '84 and promptly ingratiated himself to his teammates. "They called me Country Boy...they thought Texas was a hick state."

Brown arrived on Campus in the fall of '84 and promptly ingratiated himself to his teammates. "They called me Country Boy...they thought Texas was a hick state."Tim saw the field as a freshman, playing third-string wide receiver and returning a few kicks. He got off to an ignoble start -- in his first game, he fumbled a kickoff and Purdue recovered.

The Boilermakers got 3 cheap points off the turnover, and ended up winning 23-21. Brown wasn't fazed. “I knew what I could do. It was just a matter of bouncing back.” Brown finished 1984 tied with Milt Jackson as the #2 receiver on the team.

The next year he started to make a few waves. Against Michigan State, he would return the first of many kickoffs in his career, a 93-yard beauty. It was the first Irish kickoff return for a TD in three years. Later in the game, he caught a 49-yard pass that set up another Irish touchdown.

Still, the Irish were laboring under the inept leadership of Gerry Faust, and were getting booed at home routinely. The offense was mostly a predictable and boring reliance on Allen Pinkett, a great talent, but over-utilized (immortalized in the slogan known to many Irish fans of that era: "Pinkett, Pinkett, Pass, Punt").

For Brown, the two years under Faust were “really tough. It’s nothing against him. He’s a great man and he did all he could. I just felt he was really in over his head.” Faust was fired and replaced by Lou Holtz after the season ended, and for Brown, this would prove to be quite fortuitous.

---------

“Who’s 81? He’s good." -- Beth Holtz.

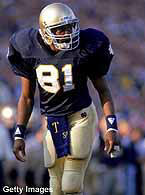

When Lou Holtz arrived, everything changed for Brown. And for Holtz, discovering No. 81 on the roster was like finding a diamond in a coal mine. Holtz quickly decided that Brown was being underused, and found there were plenty of ways to get him involved in the offense. In addition to keeping him on the return teams, he bumped him up to first-string receiver, and even put him in at tailback in some wishbone formations.

When Lou Holtz arrived, everything changed for Brown. And for Holtz, discovering No. 81 on the roster was like finding a diamond in a coal mine. Holtz quickly decided that Brown was being underused, and found there were plenty of ways to get him involved in the offense. In addition to keeping him on the return teams, he bumped him up to first-string receiver, and even put him in at tailback in some wishbone formations.“After three days of spring practice, I made the comment that Tim Brown may be the best football player I’ve ever seen," Holtz said. "He just grasped things. He has an awareness on the field of what he needs to do. He knows the down and distance and when to try to outrun someone and when to cut it back. It’s nothing you can teach or coach.”

This would be the dawning of the classic hybrid role that Holtz would install time and again, first with Tim Brown, and later with the Rocket.

It was the annual game against USC that really launched Brown's reputation as a premiere college football player. On that Thanksgiving weekend at the Coliseum, Tim had a 57-yard kickoff return, a 49-yard catch, and a 56-yard punt return. Brown had 13 touches and 252 all-purpose yards.

He finished out 1986 with 45 catches, 846 receiving yards, and 254 yards rushing on 59 carries, and 698 kickoff return yards, for a total of 1,937 all-purpose yards. He scored 9 touchdowns: 5 receiving, 2 rushing, and 2 on kickoff returns.

Brown had mixed feelings about running the ball out of the backfield. “I like running the ball because you have a chance to see where everybody’s going. But at this level, I don’t think I could take the punishment. "

Holtz agreed. “He’ll run physically, but if he does it on a continuous basis, he will not be the same player he is.”

-----------

“What a move Timmy put on him. I don’t know where a dance is being held tonight, but that’s the only place you might see another move like that.” -- Lou Holtz.

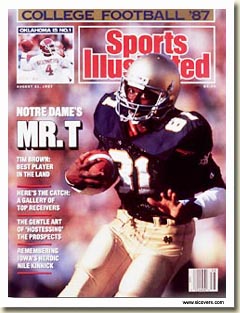

“What a move Timmy put on him. I don’t know where a dance is being held tonight, but that’s the only place you might see another move like that.” -- Lou Holtz.1987 was the pinnacle of Brown's collegiate career, and the game against Michigan State was his finest moment. He returned not one, but two punts against the Spartans.

The first return was 71 yards, a beautiful tackle-breaking jaunt helped along by two key blocks. At one point Spartan cover man Todd Krumm taunted Brown as he ran up the field. "He was saying, Come on, come on," Brown related later. "So I came to him." One swivel-hip fake later, and Krumm was left in the dust.

The second return was shorter (66 yards) but much more impressive. ND put on a 10-man rush, and Brown had no blockers. In fact, “I was supposed to call for a fair catch” Brown said later.

“But we knew Greg Montgomery [MSU punter] had a 53-yard average. We figured he’d overkick the coverage, and that’s exactly what he did.”

Brown said he was going to run the return out of bounds for a short gain until he sensed the Spartans were overflying their mark. In a flash, he burst past all seven. He beat three others then raced toward Montgomery, the last defender.

“One and then another ran past me,” Brown said. “Then another one left his lane, and pretty soon it was just me and the punter.”

“I had to beat the punter. If I got tackled by the punter, I knew I’d hear it from my teammates.”

With a fake and a dodge, he put a beautiful move on Montgomery that buckled his knees and sunk him to the dirt.

Brown also caught 4 passes for 72 yards in the game. All told, he touched the ball 14 times for 275 all-purpose yards, and cemented his reputation as a legitimate Heisman candidate.

Brown was typically modest. “I think this game might have helped me out a little, but I think our defense deserves it more. They gave us field position.”

A few games later, Brown got to showcase how well he played without the ball. Against USC, he was held to only 109 all-purpose yards. Trojan coach Larry Smith had ordered squib kicks and high, short punts. Said Smith, “I’ll give them 10 yards on a kick with no return. I’m no dummy.”

Instead of carrying the offense, Brown threw several key blocks that paved the way for Irish scores.

He also had a long catch called back when an overzealouos referee called the play dead a little too early.

“The official told me it was an inadvertent whistle," Holtz said. "I couldn’t blame him. It’s natural from somebody who hasn’t seen much of Timmy Brown to think, on a play like that, ‘There ain’t no way that sucker can get out of this one.’”

-------------

“It’s nice to pick up a magazine and see my name mentioned with the Heisman, but star-gazing can hurt you. My feeling is if it happens, it happens.” -- Tim Brown

As 1987 wound down, No. 81 found himself the subject of deserving, but intense Heisman hype. Yet, none of it came from Notre Dame, or Brown himself.

As 1987 wound down, No. 81 found himself the subject of deserving, but intense Heisman hype. Yet, none of it came from Notre Dame, or Brown himself.The low-key response was vintage Brown. “No, I’m not worried about it. I’m only concerned that we keep on winning and that I go out and play good. They were talking about me winning the Heisman, but I think those guys (the defense) deserve it.”

Holtz, perhaps in a bit of creative oratory, seemed to downplay it while bringing it up. “We don’t plan on doing anything special for Tim Brown and the Heisman award.”

Still, the hype was there, and as often happens when you get too much of a good thing, national sentiment turned against him late in the season. Brown heard a lot of reasons why he wasn’t worthy. There was focus on a couple of dropped passes, some terrible losses against Miami and Penn State. As the year went on, teams started to short kick him, kick it away or squib it, and his all-purpose yardage totals started to diminish.

“Air Force kicks two out of bounds and three more so high I had to call for fair catches. The one I returned, I kind of thought he was trying to kick it out of bounds, too," observed Brown. He had 25 return opportunities in ’86; only about half that in 87.

Furthermore, there was a sentiment that the whole idea of "all-purpose yards" was somehow illegitimate.

As one letter to the editor put it, “How long will the nation’s sportswriters let themselves be duped by the inflated 'total yards' statistic pumped out by the ND publicity department on the behalf of Tim Brown? Total Yards includes kickoff return yards which, for each kickoff, contains about 20 yards of running through empty space before meeting any tacklers. I am a 38-year-old executive and even I could lumber for 15 yards per kickoff return."

Pitt fullback Ironhead Hayward, a Heisman candidate himself, jumped into the fray. “I thought the Heisman was supposed to be somebody who dominated his position, not somebody who runs all over the field playing hide and seek.”

Mike Downey of the LA Times wrote, “If TB played for any other school, there is no way he would have a shot at the Heisman. His statistics just didn’t measure up." And yet, in the end, Downey argued that there was nobody more valuable to his team than Brown. “So there is nothing wrong with awarding the Heisman to someone who was extremely valuable to his team, as Tim Brown has been, rather than someone who just piled up better statistics.”

Brown essentially concurred. “I’m not going to apologize for going to ND. I went there because I felt I could better myself as a person, and I found out it helped me in football also.”

--------------

"He’s incredibly valuable -- even when he doesn’t get the ball.” -- ND Heisman winner Leon Hart

In the history of the Heisman, runners and passers dominate. Even in the heyday of the two-way athlete, almost every winner was primarily a running back or a quarterback. And so it was something of an anomaly that Brown would win. He was only the 3rd receiver to take the award, the others being Johnny Rogers in 1972 and ND's own Leon Hart in 1949. Brown finished way ahead of the second place honoree, Don McPherson of Syracuse (the perennial trivia answer Gordie Lockbaum of Holy Cross finished third).

In the history of the Heisman, runners and passers dominate. Even in the heyday of the two-way athlete, almost every winner was primarily a running back or a quarterback. And so it was something of an anomaly that Brown would win. He was only the 3rd receiver to take the award, the others being Johnny Rogers in 1972 and ND's own Leon Hart in 1949. Brown finished way ahead of the second place honoree, Don McPherson of Syracuse (the perennial trivia answer Gordie Lockbaum of Holy Cross finished third).Although they were both receivers, Hart and Brown couldn’t have been more different. Hart was 6’5 and weighed 252 pounds, which was gargantuan for his era. He was a “giant end” who played both offense and defense.

Yet Hart admired Brown. “The important thing with Tim Brown is, he affects the game so subtly that anybody with a trained eye can see what’s occurring when the other team doesn’t kick to him and they loft the ball on a punt so that the teammates can get down under it. They only kick a 25-yard punt instead of a 40-yard punt, and Tim gained 15 yards just by standing there. So he signals for a fair catch and actually gains yards.”

“But the important thing is what Holtz does with him," Hart explained. "His talent is such that they double- and triple-cover him, they put him out wide to the right and then run the option opposite Brown, and the defense doesn’t have enough men left over the cover what ends up as the QB and the pitch man."

Brown responded to the award in his typical modesty, and shared the award with his team. “I thank God, and my coaches and teammates. I said from the start, this was a team award. It would not have been possible if they did not block for me or pass the ball to me. God bless you all, and thank you very much.”

Although the Heisman award is still populated by mostly QBs and RBs, Brown did pave the way for the consideration of other positions for the award, and both Desmond Howard and Charles Woodson owe a lot to his legacy.

(Random Heisman fact: an ND player has finished among the top 10 in Heisman ballotting 35 times in the 68-year history of the award.)

--------------

"I got my towel back. That was that.” -- Tim Brown

Perhaps the low point of Brown's career -- and it wasn't even that low, despite the negative publicity that surrounded the incident -- happened during the Cotton Bowl against Texas A&M in 1987.

In the 4th quarter, Brown was tackled on a kickoff return. After the whistle sounded, he chased an A&M player and tackled him from behind because he had stolen his towel.

It was a blue towel with gold trim and a “T 81” embroidered on it. A gift from teammate Cedric Figaro.

The towel thief was Warren Barhorst, a non-scholarship player who is the infamous “Twelfth Man” on A&M’s kickoff coverage team – a longtime tradition in A&M lore, where a student walk-on plays on the kickoff coverage team.

The score was already 28-10 when Brown was tackled and Barhorst landed on top of him.

Brown got up and ran about 20 yards towards the Aggie bench to catch up with Barhorst. Brown jumped on his back and fell with him to the ground. Benches cleared and surrounded the scuffle.

“Evidently, they had something planned on the sidelines. One guy held me down, and another guy took my towel. I didn’t mean to tackle him. It looked like I tackled him, I know. But I got my towel back. That was that.”

Brown did his part in the game. Returned the opening kickoff 37 yards, caught 10 passes, including a TD, and finished with 238 all-purpose yards. But ND got crushed, 35-10.

Incidentally, Barhorst had been in on only 5 kickoffs all season, and when he landed on top of Brown, it was his first (and last) college tackle. “What a way to end my football career,” Barhorst exclaimed jubilantly.

Brown is a first-ballot NFL hall-of-famer. Wonder what Warren Barhorst is up to these days.

--------------

“I’ve never seen anybody in this football game like Timmy Brown. His mere presence…his leadership...his blocking...the things he does without the ball.” -- Lou Holtz

Brown left ND as the all-time receiving leader with 2,493 yards. He accounted for 5,025 all-purpose yards, scored 22 touchdowns, and averaged 116.8 yards per game over his entire career.

Yet in a continuation of what seems a lifetime of underappreciation, many pro scouts were poo-pooing his accomplishments. Some were trumpeting Michael Irvin, Anthony Miller, or Sterling Sharpe as better pro prospects. Said Tampa Bay coach Ray Perkins of Sharpe, "He's more of a football player [than Brown]."

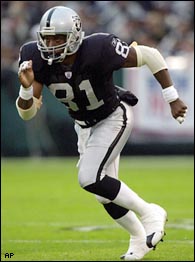

Brown ended up going 6th overall, to the Los Angeles Raiders. Aundray Bruce, Neil Smith, Bennie Blades, Paul Gruber, and Rickey Dixon were all picked ahead of him. Sterling Sharpe went one spot later, and Michael Irvin went 11th.

------------

Brown and the Raiders couldn't agree on a contract right away, but Brown, in an act that seems completely foreign to NFL fans these days, still reported to camp anyway. He signed a temporary 1-year deal at half the going rate just to get in camp and get started (later he agreed to a 4-year, $2.8 million deal.)

Brown and the Raiders couldn't agree on a contract right away, but Brown, in an act that seems completely foreign to NFL fans these days, still reported to camp anyway. He signed a temporary 1-year deal at half the going rate just to get in camp and get started (later he agreed to a 4-year, $2.8 million deal.)In his first regular-season game with the Raiders, he returned a kickoff 97 yards for a TD. By the end of the year, he had broken Gayle Sayers’s league record for total yardage by a rookie with 2317 yards. He racked up 725 receiving yards, 50 rushing, 1,098 on KO returns and 444 on punt returns.

He was named to the Pro Bowl as a rookie kick returner, and also won the Rookie of the Year.

Jim Murray, the great sportswriter of the LA Times, looked back on the low expectations for Brown following his selection by the Raiders:

“So, the Raiders sighed and took what they could get. In this case, it was Timothy Donell Brown, of the Dallas, Texas, Browns, a nice enough young man, soft-spoke, dependable. He’d gone to Notre Dame, which was good, but he was a kind of what-is-it quantity on the football field, which wasn’t.

Then, too, he had won the Heisman Trophy. Now for those of you who think this would be a big plus, you haven’t been paying close attention. Heisman winners have historically been something less than sensational in the pros…besides, there was a notion that for a Notre Damer to win it, all he had to do was be able to frost a glass and not fumble too much.

It’s hard to believe the Raiders didn’t have high hopes for this terrific Tim. But kickoff specialists are a dime a dozen in the NFL. Even Brown’s Heisman didn’t stand out: there were three of them already on the team.

It’s hard to think of a Heisman-Notre Dame luminary, the most celebrated college player of his season as a surprise in his pro debut. But Tim Brown has made a lot of NFL owners look frowningly at their general managers.

Who would have thought you’d get a star like this out of a Heisman? Here’s a guy who started at the top and went up, who rose above the adversity of reputation. Before him, all-purpose used to signify a guy who did a lot of things – with mediocrity. Tim Brown does so many things so well, the Raiders should just be glad he never took up baseball."

In the first game of 1989, he blew out his knee and missed the rest of the season.

------------

“I hate that I have to ask to play football, but if it comes down to that, I’m going to do whatever it takes to get me on the field.” -- Tim Brown

Recovering from the injury took a lot longer than Brown anticipated, even after it was completely healed. He found that when he returned the team, he wasn't nearly as involved in the offense, and he soon was begging for playing time.

To be sure, he wasn't a "me-first" player by any stretch, not Keyshawn saying "give me the damn ball." Rather, he felt like he could contribute, and he didn't think he was doing enough.

“Every time you lose, you can’t help but ask yourself, ‘Is there anything more I could have done?’ Then, it starts to become an ego thing.”

Later, he explained how he went to talk things over with Al Davis. He described what the eccentric Raider owner said to him, mimicking his drawl: “Ya doing aw great job, Timmer, just keep it up. We love ya.”

But Al loved breakaway speed, long bombs and track stars. Willie Gault – fast as lightning, running the streak pattern -- was his prototype, not a dependable but boring over-the-middle possession guy like Brown. Brown was frustrated and contemplated leaving.

He thought a clause in his contract would make him a free agent after the season, but the commissioner ruled in the Raiders favor, and he was stuck with the team for another two years.

But rather than slinking into training camp and pouting his way through the season, Brown took the opposite approach. “I prepared myself harder than I ever have in the off-season. And I worked harder than I ever did in training camp. I wasn’t going to get the money, but I still play this game because I love it.”

He gradually worked his way back into the offensive scheme, and established a great chemistry with new Raiders QB Jeff Hostetler.

Jim Murray again, looking back on this period:

“The Raiders didn’t quite know what to do with Tim. He was a wide receiver but he also returned punts and kickoffs. Stumped, they put him on special teams.

Al Davis’s quarterbacks were known as mad bombers, blitzkriegers. His teams didn’t need the ball much. Let the other guys push it up through the mud. Davis’s teams struck like cavalry.

They had some trouble seeing Tim Brown in this scheme. Tim is not going to anchor the Olympic relay team. They liked his moves – on kickoffs and punts. They were less sold on fly patterns. One year, in 1991, he started only one game.

But gradually, one thing began to dawn on this Raider brain trust: When he was in there – usually on third and long – Brown would be as wide open as Dodge City on a Saturday night.

Brown perfected his craft. He studied defenders the way a pitcher studies hitters, but mostly he studied coverages. He found the soft spots, the open spaces in his opponents’ zones. He exploited them.

And now, Tim Brown is striking a blow for Heisman winners everywhere."

In ’94 he had his best season to date. He caught 89 balls for 1,309 receiving yards and made the Pro Bowl for the first time as a receiver, not just a special teams player.

In ’94 he had his best season to date. He caught 89 balls for 1,309 receiving yards and made the Pro Bowl for the first time as a receiver, not just a special teams player.And from there, he was simply one of the best players in the league for over a decade, and one of the best players in the history of the game.

Brown went on to capture almost all of the Raider franchise records: most pro bowls, most touchdowns, most receiving yards, most receptions, most yards from scrimmage, most punt returns, most 1,000 yard seasons (9).

- Led the Raiders 11 times in receiving yards.

- Was the only raider to score on a run, a reception, a punt return and a kickoff return.

- Went to 9 pro bowls.

He's 2nd all time receiving yards in the NFL, after Jerry Rice.

He's 3rd in receptions all-time – and he could move up to second with 7 more catches.

And he's tied for 3rd in receiving touchdowns (100).

-----------

Last year, Brown was let go by the Raiders, and he elected to sign a one-year contract with the Tampa Bay Buccaneers rather than retire. At the press conference to announce he would no longer be a Raider, Brown was his usual honest, gracious self.

Last year, Brown was let go by the Raiders, and he elected to sign a one-year contract with the Tampa Bay Buccaneers rather than retire. At the press conference to announce he would no longer be a Raider, Brown was his usual honest, gracious self.“This is a very emotional day for me. I gave my heart and soul to the organization. I battled as much as I possibly could on the field, and tried to restore the image off the field. Obviously coming in here, me being a Notre Dame guy, everybody said that I didn’t fit in here as the typical Raider. I have thoroughly enjoyed my career here. Mr. D and I have not always seen eye to eye, but we have always had respect for each other.”

For his part, Al Davis praised Brown. “One of the truly great players who has ever played the game, and obviously one of the truly great players that has ever played for the Raiders.”

-----------

“One thing I have never done is take the game for granted. I have always known that any given play could be your last.” -- Tim Brown

On Saturday, the Tampa Bay Tribune reported that Tim Brown will be joining Charlie Weis's staff in some capacity this year, although exactly what his role will be is dependent on if he chooses to play another year in the NFL at the same time.

"I will have some title there,'' Brown said of Notre Dame. ''And whatever the title is, it won't interfere with me playing ball - whether I play ball or do TV or whatever.''

Brown met Thursday with Notre Dame athletic director Kevin White to discuss aiding the Irish in their attempted return to prominence.

Brown's role likely will be decided during a future meeting with new coach Charlie Weis.

''Charlie's not in the loop right now,'' Brown said, referring to Weis' role as offensive coordinator of the New England Patriots. ''Once he's out of the playoffs, after the Super Bowl, we'll be able to come up with an official title and see if I can help with recruiting or be a player liaison or something so players there can have an outlet.''

Brown said it might be another month or two before he decides whether to retire as a player.

''I don't know if I'll make a decision before March or not,'' he said.

Brown said he intends to devote a lot of time to the Irish program if he decides to retire as a player.

'If I'm not playing I can have a lot more of an impact,'' he said. ''If I do decide to play ball, then it's up to what Charlie wants me to do. After the playoffs we'll have a chance to iron some things out.''

Whatever the exact timeline happens to be, it seems certain that Tim will be returning to ND, and fairly soon. Even if he plays another year in the NFL, it looks like he's pretty close to retiring, and when he does, we can expect his role and responsibility for the Irish to be substantial.

For a while in the mid-90s, I worked in El Segundo, California, where the Raiders had their practice facility, and I used to see Tim out at lunch a couple of times a year. Always had a smile for me when I mentioned the ND connection; always was gracious in talking to anyone who recognized him and said hello.

Like most fans, I remember Tim Brown for his great catches and his electrifying kick returns. I remember the games and the touchdowns, the Heisman award and the towel incident. I remember liking the Raiders just a little bit more when they drafted Tim, and I remember feeling some gratification that Brown was one of the few Heisman winners to actually live up to his billing.

But I'm glad I had the opportunity to take a look back over his career, and dig up some stories that maybe I'd missed or I'd forgotten. The complete picture of Tim Brown, the person, is one of not just God-given talent, but incredible honesty, integrity, and perseverance.

I can't imagine a better homecoming and sense of personal satisfaction for Tim in this next stage of his professional life, nor can I imagine a greater benefit for the University than having No. 81 back on campus. Congratulations, Tim: another brilliant run is about to begin.